Fault Lines #6: Présidente Le Pen?

France may yet elect a far-right President. Frexit in all but name would be the likely result.

L’exception française

After the conclusion of the first round of the French presidential election on April 10, the runoff between incumbent Emmanuel Macron, and his challenger Marine Le Pen is harder to call than any recent contest. While polls are moving in Macron’s favour, there are too many uncertainties when it comes to turnout, abstentions and where the votes of the left will go to predict the outcome with confidence.

What are the underlying political, economic and social dynamics that have brought the prospect of a far-right president closer than at any time since the second world war, and what are the implications for France, Europe and the international order?

To understand how we have arrived at this precipice, it is important to appreciate just how distinctive its political, economic and security regimes are. L’exception française is real, and it reaches well beyond the orthodox caricatures of dirigisme and the social model.

The Fifth Republic creaks

“By replacing the national representation with the notion of the leader’s infallibility, General De Gaulle concentrates the nation’s interest, curiosity and passions on himself and depoliticises the rest.”

- Francois Mitterrand, ‘The Permanent Coup d’Etat, 1964

France’s Fifth Republic was borne out of the chronic political instability of its predecessor which reached its culmination in the political crisis over Algeria in early 1958 and the prospects of either a right-wing military coup or a Communist-popular front alliance on the left.

The installation of De Gaulle as president in May 1958 was a type of coup, whose legitimacy hinged on the reality that France’s political, military and security elites had lost confidence in the previous regime to resolve the Algerian crisis without triggering a civil war. The ‘republican monarchy’ that grew out of these events, copperfastened by the 1962 constitutional amendment to elect the president by universal suffrage, consolidates an enormous power in the French presidency that is unique in Europe.

In the post-De Gaulle era, the monarchical aspects of the presidency were tempered by a relatively strong party system in the shape of the Gaullists and the socialists and regular periods of ‘co-habitation’ between presidents and parliaments from opposing parties. The remarkable decline of the traditional parties, with both receiving below the 5% threshold in the first round on April 10, has emboldened those critics, in particular, the third-placed candidate, Jean-Luc Melenchon, who argue that a president-king with a purely personal mandate is ill-suited to the governance of an increasingly diverse and divided republic.

For now, questions about the reform of the fifth republic will have to wait until after the election. However, it seems increasingly clear that the combined effect of the destruction of the established political parties and the uniquely powerful nature of the presidency is central to the political dysfunctions of the French system of government.

The Quest for Grandeur

“France’s vocation is to work for the general interest. It is while being fully French that one is the most European, that one is the most universal. France is the light of the world, her genius is to light up the universe.”

- Charles De Gaulle, 1963

Since the foundation of the fifth republic, the exceptionalism of France’s political constitution has been matched by its determination to pursue a singular path in world affairs, underpinned by the imperative of ‘grandeur’ enunciated by de Gaulle in his War Memoirs.

While de Gaulle never properly defined grandeur, Julian Jackson, in his indispensable biography of the general, argues that in practice it amounted to an ongoing quest for French ‘independence’ in the front rank of nations. The paths France has pursued in foreign policy and industrial development in the post-war era attest to this.

In its security and defence policy, France has remained part of the Western alliance, despite leaving NATO’s integrated command structure in 1966 and only rejoining in 2009. Since the exit of the UK, it is the EU’s only nuclear power and its most capable military. However, French determination to pursue an independent foreign and security policy has been tempered by both a realism about the constraints it faces as a medium-sized power and a commitment to alliances. Since de Gaulle’s time, every French president has had to pull off the trick of playing an indifferent hand to the greatest effect.

Increasingly they have sought to leverage the EU to project French power. While de Gaulle envisaged a European political union of nation-states - a baton Le Pen now runs with - and was dismissive of common European defence arrangements, Macron has sought to ground the notion of greater French sovereignty in the wider idea of European strategic autonomy.

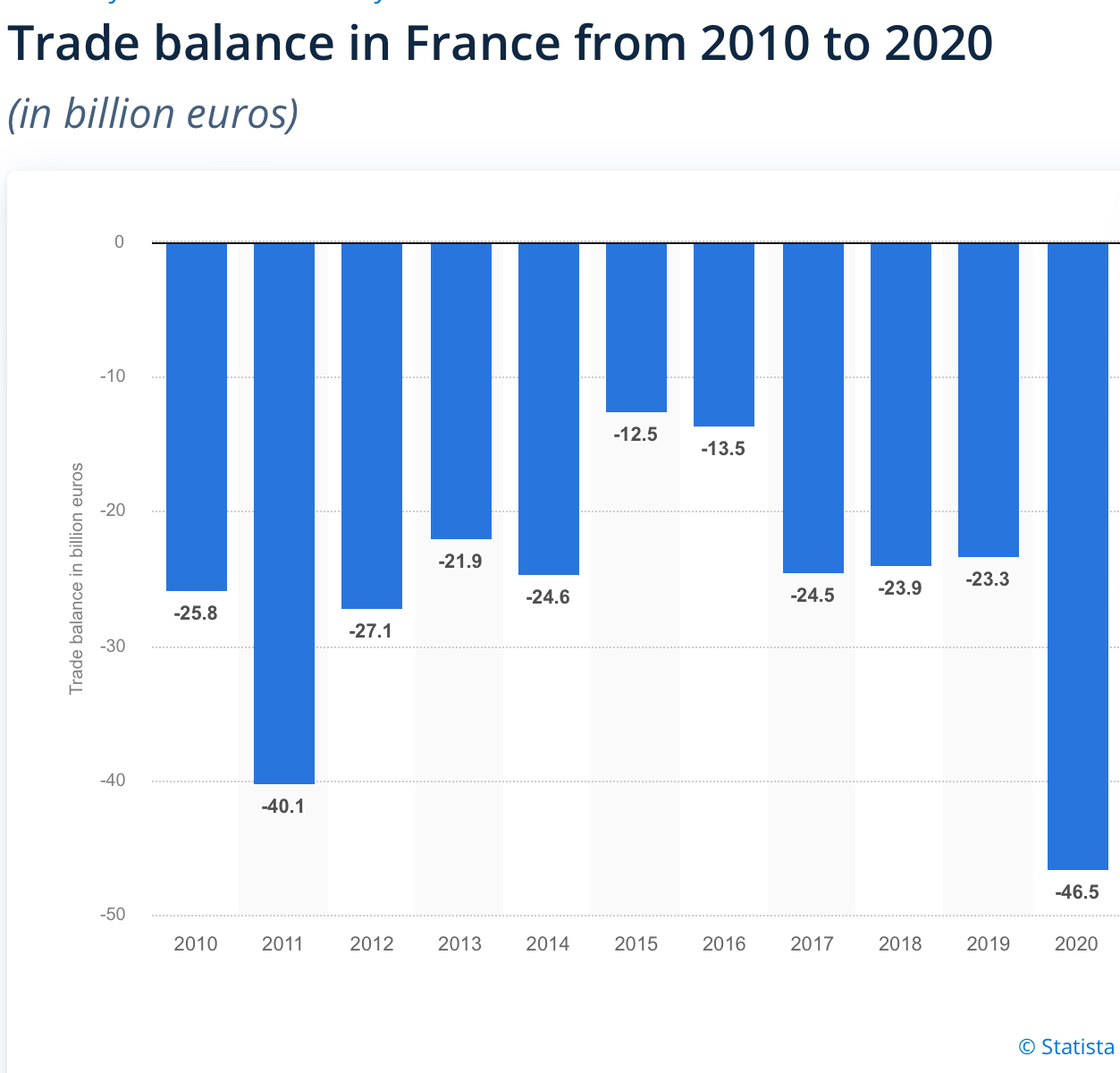

Contradictions also abound when it comes to the economy. The inescapable logic of the Eurozone has been to make all members pursue trade surpluses in imitation of Germany by prioritising competitiveness over investment. Leaving aside the wisdom of this approach, it is striking how France stands apart from the dominant export-led model of the bloc with the country running consistent trade deficits over the past decade culminating in a record goods deficit of €84.7bn last year.

In addressing the latest deficit, Macron’s Finance Minister, Bruno Le Maire said the figures highlighted “the industrial weakening over the past 30 years”, but pointed to progress under the current administration with “a more favourable tax environment, by lowering production taxes, by training and qualifying employees for new industrial professions. There was no other solution, he added to restoring France’s external trade balance than “to reindustrialise our country massively and quickly.”

Despite its long industrial decline, France retains significant economic strengths over its EU counterparts, in the quality of its larger companies, its nuclear-led energy system and its self-sufficiency and security in food.

However, for all the headline improvements Macron has made to French economic performance, as measured in strong economic growth and unemployment at its lowest since 2008, this masks the inevitable effects of the decades of industrial decline that Le Maire acknowledges: left behind towns and regions, skilled blue-collar jobs being replaced by lower-skilled or unskilled occupations and a pervasive sense of economic insecurity.

The clear political danger for Macron, a president who more explicitly seeks to invoke the spirit of Gaullist grandeur than his predecessors, is that his protection of somewhat abstract ideas of France comes across as an indifference to the plight of the average voter in thrall to Le Pen’s promises.

A dangerous people

“Ce peuple, apparemment tranquille, est encore dangereux.”

- Raymond Aron, 1978

Le Pen’s rhetoric of prioritising the real French people over both internal and external enemies, personified by Macron as the ‘President for the Rich’, mines a deep vein of outsider politics in France, drawing on the Poujadist movement of the late Fourth Republic.

Like the Gilets Jaunes of recent years, Poujadisme was first and foremost a tax revolt that championed the cause of the ‘braves gens’ the small producers and shopkeepers like Pierre Poujade himself, whose livelihoods were threatened by the disproportionate power of the state.

The throughline to Le Pen is exemplified by the fact that her father, Front National founder Jean-Marie, was the youngest member of parliament elected for Poujade’s Union de Défense des Commerçants et Artisans. Although Le Pen père was later disowned by Poujade for his racism and lavish lifestyle that gave a lie to his empathy for the suffering of the ‘little people,' the most striking aspect of Marine Le Pen’s project to detoxify her father’s party has been the manner in which she has brought the concerns of Poujadisme to the centre of the agenda.

While the traditional hardline stance on immigration is present, it is less prominent than promises to exempt all young workers up to the age of 30 from income tax, abolish inheritance tax for “modest and middle-class families” and reductions in petrol and electricity taxes.

Poujadism was blown away by the return of de Gaulle and the birth of the fifth republic in 1958. It is a puzzle why Macron, so close a student of the general and his attachment to the village life of Colombey-les-Deux-Églises, failed to ground his own project of national renewal from 2017 onwards on the needs of ‘la France profonde’, as many previous presidents have.

Worryingly for Macron, as Sudhir Hazareesingh astutely observes in his marvellous ‘How the French Think’, the one exception that proves the rule was Nicholas Sarkozy, whose exoticism and suburban hauteur condemned him to a single term of underachievement.

Macron’s inability to escape the elitist labelling of his opponents masks a track record that is far from Anglo-Saxon laissez-faire. The anger of large sections of the lower-paid in France arises in large part from unhappiness about the amount of tax they pay to fund the very social model they wish to defend and accuse Macron of dismantling. For every SNCF driver who retires at 52 or pensioner who demands a full pension at 62, there is a small business owner who plans to vote for Le Pen because she promises to cut taxes while improving social security.

While the writer Sylvain Tesson may be half-correct when he says, “France is a paradise inhabited by people who think they’re in hell”, these nuances cut little ice in what the journalist John Lichfield calls “France’s 30,000 angry villages” or the peripheral France spotlight in this excellent report from The Economist:

Auchy-les-Mines is too far from Lille to be linked to its public network of trams or suburban railways. Buses are the only form of public transport. Most villagers rely on cars, and many of the small two-storey brick homes have off-street parking spaces or a garage. The rising cost of fuel is a worry, and residents treat the anti-car crusades by Green politicians in big cities as an affront. In Auchy-les-Mines, where 85% of households own at least one car, locals resent the idea that they should be punished for using them, as Mr Macron found to his cost when the gilets jaunes (yellow jackets) uprising broke out in late 2018.

The hope for Macron in the runoff is that a significant proportion of Mélenchon’s vote is not so ideological as to be off-limits to him and that this outweighs the near certainty that Zemmour’s vote breaks for Le Pen.

The very different sociological profile of Mélenchon’s electorate over that of Le Pen as outlined by Alexandre Afonso in his excellent newsletter, which is a must-subscribe, spells out how this more diverse and urban vote might break decisively for Macron:

It is interesting to note that the relationship between the proportion of workers and the share of the Mélenchon vote is negative, in contrast to what we observe for Marine Le Pen. This is a surprising result insofar as we often consider that Mélenchon and Le Pen are courting the same popular electorate, and that a non-negligible proportion of Mélenchon voters declare that they want to vote for Le Pen in the second round. Yet the constituencies where the two candidates obtain their highest scores are very different from a sociological point of view. Le Pen gets a higher score in areas dominated by the traditional white working class (especially in Northeast France), whereas Mélenchon does (much) better in more ethnically diverse, urban and young areas.

The risk, as Philippe Marliere outlines in openDemocracy, is that the left will divide equally between Macron and Le Pen in the second round, with the remainder abstaining. With the addition of Zemmour’s supporters, that might be just enough to swing the outcome for Le Pen in a tight contest.

Many left-leaning voters, who have been disciplined enough in the past to vote for a conservative candidate to ‘stop fascism’, appear to have now had enough. Opinion polls show that up to a third of Mélenchon’s first-round voters would currently opt for Le Pen in the second, while up to another third would abstain. These figures do not look good for Macron, who will have to listen to and win over this electorate. He cannot afford to be complacent.

The threat is all the more real given that some left-wing candidates, including Mélenchon, do not want to explicitly call on their supporters to vote for Macron. “We know for whom we will never vote! You must not give your vote to Marine Le Pen!” Mélenchon told his supporters on Sunday evening. The message was widely interpreted as implicitly condoning abstention, which would facilitate Le Pen’s victory.

The old anti-fascist reflex is fading away on the Left, the conservative electorate has radicalised, Zemmour has further mainstreamed racism in French society and Le Pen has softened her image. Macron, meanwhile, is the sole target of a volatile and angry electorate. The conditions have been set for France to sleepwalk into a far-Right presidency. This was not a possibility before. It is now.

Realising somewhat belatedly that he faces an entirely different challenge from Le Pen this time around, Macron has acknowledged that the default strategy of the political establishment of demonising the far-right will have limited traction against an opponent that a majority of French voters no longer see as an existential menace to the Republic:

Macron’s declared intention to wage a "proposal against proposal" battle against Le Pen and dismantle her promises "point by point", while outlining the real consequences if she were to be elected, carries a whiff of previous attempts to scare electorates, most notably the failed ‘Project Fear’ strategy during the Brexit referendum.

It risks falling short against an opponent whose campaign seems to have captured the anti-elite mood of, to paraphrase Raymond Aron, an apparently tranquil public that has become increasingly dangerous to the political establishment, irrespective of her ability to actually enact her programme if she does reach the Elysee.

Whatever the outcome, the action is likely to move swiftly to the streets. As the renowned political commentator, Alain Duhamel said, “Whoever is elected president will have no sociological majority. The biggest political force in France today is ‘dégagisme’ (get out-ism).”

Frexit in all but name?

"Europe is the means by which France can become again what she has ceased to be since Waterloo: first in the world.”

- Charles De Gaulle, 1962

While France is a founding member of what is now the EU, it has often been as much a brake on further European expansion and integration as an enthusiastic advocate for this. While the Russian invasion of Ukraine has dramatically shaken up the question of the EU’s expansion, as recently as 2019, Macron vetoed the start of the accession process for Albania and North Macedonia.

France has consistently deployed l’exception française to resist aspects of European integration, most famously in the ‘empty chair’ crisis of 1965/66, where De Gaulle withdrew from the Community institutions after the Commission overplayed its hand by attempting to directly collect import levies to fund the Common Agricultural Policy.

The compromise that was ultimately reached prevented majority decisions where national interests were at stake: described by Julian Jackson as a “decisive brake on the process of European integration.” For de Gaulle, European integration was something that had to remain subsidiary to the predominant interest of the nation-state, telling one of his ministers at the time of the crisis that:

“We have lived for many centuries without a Common Market. We could live several centuries more without a Common Market.”

Of course, de Gaulle was dealing with European integration as it was then; most likely he would be appalled at what is now the EU has become, given his abiding belief that supranational organisations could not have political authority. French policy has been transformed since his time, with the country’s membership of the single market and the Eurozone and Macron’s vanguardism for deeper European integration on defence and fiscal policy. French elite opinion sees the project of European integration as the best means of projecting French power.

Whether these elite positions are shared by the French public is another question, and one Le Pen’s campaign may test to its limit. She argues for the so-called ‘National Preference’, which would permit discrimination against other EU citizens living in France in social and economic policy. Being in breach of both French and EU law, such an approach would open up a direct confrontation with the EU institutions and in order to implement it, Le Pen would have to propose a constitutional referendum.

Might such a referendum lead to Frexit in all but name if successful? For Mij Rahman, one of the sharpest analysts of European politics and policy and a must-follow, the answer is clear:

Forget Brexit, here comes Marine Le Pen

Though Le Pen now claims she does not want to leave the EU, almost all of her economic program, and much of her social and migration policy, depends on breaking EU laws. However, she does not openly recognize this fact, relying instead on the widespread ignorance of many French voters on how the EU works.

She is, in effect, saying she wants to remain aboard the EU bus — but drive it off a cliff. A close look at Le Pen’s program highlights its incompatibility with EU membership: By way of a constitutional amendment, Le Pen would seek to make it possible to discriminate against foreign residents, including EU residents, in terms of jobs, welfare and housing. She would withhold €5 billion per year in payments into the EU budget, give preference to French businesses on all national and local government contracts, and extra subsidies to French farmers. She also says she’d reimpose checks at France’s land borders with Belgium, Luxembourg, Italy and Spain.

All these policies would break EU laws and threaten to destroy the single market. If implemented, they would undoubtedly bring legal action and financial retaliation from both Brussels and domestic courts, causing the greatest crisis in EU history. France, in the heart of Europe, could find itself isolated, or the leader of a small group of dissident nations.

The difficulty for Macron in all of this is the same as that of many European leaders whose disposition is to see the process of greater European integration as a sine qua non in a multi-polar world that is breaking into separate blocs anchored by regional powers. As the unlikely philosophe of the European politics, former Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker put it: “We all know what to do, but we don’t know how to get re-elected once we have done it.”

Indeed on the only recent occasion when French voters were asked to endorse moves towards greater European integration - in the Constitutional Treaty referendum of 2005 - they decisively rejected it. It is distinctly possible that Le Pen’s advocacy of a '“Europe of nations” that takes powers back from the centre is more representative of the perspective of the median French voter than Macron’s quest for an ever closer union.

In practice, Europe will not receive much attention from voters. In eschewing the detail of what Le Pen proposes, there is a real risk that her policies will not be properly scrutinised despite Macron’s best efforts, as John Springford and Ian Bond from the excellent centre for European Reform argue in this piece:

If Le Pen enacted her policies, the consequences for the EU would be political chaos. France would not leave the EU and the euro in the short term, which would – with luck – mean that financial markets would not take fright. But the EU institutions and the member-states have weak powers to force her to back down: fines imposed by the ECJ could simply be ignored, and France has enough fiscal capacity to accept the freezing of EU budget and recovery fund money under the new conditionality mechanism, which punishes countries that violate the rule of law. The EU would face gridlock on a whole range of policy issues: without the ‘tandem’ of Germany and France negotiating compromises between themselves on the big policy areas, little new legislation would be passed. But the biggest problem would be that the EU might have little ability to enforce its own laws in an indispensable member-state, while nationalist governments in the EU would have much greater critical mass, and act together to undermine the EU further.

President Le Pen would pose a threat not only to Europe’s internal order, but also to its external security. Her manifesto has relatively little to say about defence and foreign policy: Russia is referred to once, indirectly (the war in Ukraine has shown that “the policy of fait accompli has gradually become the norm” in international relations). China is mentioned as the country from which COVID-19 came; the US is the only country directly criticised, for deploying its law extra-territorially. But her concrete foreign and security policy proposals would be a significant departure from the post-Cold War French approach. They are founded on folie de grandeur: having described France as the world’s second largest power by geographical extent (based on the extent of its maritime zone around French Polynesia and other Indian Ocean and Pacific territories) she calls for a policy of “free hands” – that is to say, not being tied down by alliances. That is a policy prescription for a super-power, not a medium-sized European power that has decided to undermine its partnerships in the EU as well as NATO. Even the post-Brexit UK has tried to compensate for lost influence in the EU by increasing its political and military investment in NATO and in its bilateral relationship with the US

So we should not underestimate the stakes. The war in Ukraine, the pandemic, the climate emergency and the incomplete monetary union all call for a leap forward in European integration rather than a retreat to a nostalgie pour la nation. However, as I argued in Fault Lines #5, for this to happen Treaty change must be on the table and the debate on this must be taken out of the hall of mirrors of high politics and exposed to full public view.

On April 24, we face yet another election where the outcome is said to be ‘existential’ for each side. The stakes around politics as the crises of our age multiply and exacerbate keep ratcheting up. And yet, we must acknowledge the damage that is done to our democracy by the constant delegitimisation of the other side. Our polarised political systems are ill-suited to grappling with the challenges we face: a new consensus must emerge for a politics of progress to gain ground.

The Fench political establishment, like that elsewhere in the democratic world, cannot seek to defeat a challenger like Le Pen once every five years: it must take the fight to them every day and win popular acclaim and consent for a new politics that properly confronts the general crisis of the 21st century.

April 24 should be the start of that project, not its ending.