Fault Lines #7: Ukrainskii Mir

The war in Ukraine and the West's economic war against Russia are reaching an impasse. Given the stakes for the world, would a flawed peace be preferable to a prolonged conflict?

Endgame

Three months after Putin’s illegal invasion, we have learned much we did not fully understand at the time. Russia’s military campaign has been incompetent at best, a fiasco at worst. It has sacrificed huge numbers of lives and materiel for no meaningful advance on the territories it controlled on February 24th. For now, it has dialled its war aims back to gaining full control of the two oblasts of Luhansk and Donetsk that comprise the Donbas region. Even this limited objective has proven grindingly difficult to achieve, although there are signs that Luhansk in particular may soon come fully within Russian control.

Ukrainian forces, by contrast, have outperformed expectations. The years since the annexation of Crimea in 2014 were used wisely to build up a professional and motivated army, and NATO arms supplies have made a significant difference. The expectation among many that Kyiv would fall quickly proved astonishingly wide of the mark:

Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Gen. Mark Milley told lawmakers that Kyiv could fall within 72 hours if a full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine takes place, multiple congressional sources tell Fox News.

Milley told lawmakers during closed-door briefings on Feb. 2 and 3 that a full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine could result in the fall of Kyiv within 72-hours, and could come at a cost of 15,000 Ukrainian troop deaths and 4,000 Russian troop death

However, for all Ukraine’s courage and determination to resist any advance beyond the territorial lines that stood before February 24th, the war is settling into one of attrition, with neither side able to make a decisive breakthrough. This impasse means that in the short term neither side is likely to prevail in its war aims. Equally neither is ready to discuss peace. Absent a decisive intervention, the conflict is likely to grind on.

The situation on the battlefield has led to a recalibration of the West’s war aims. The premature triumphalism of a month ago, when the US Defence Secretary Lloyd Austin stated that he wanted to see Russia weakened to the degree that it can’t do the kinds of things that it has done in invading Ukraine, has given way to confusion about how the war ends.

While Congress has authorised an extra $40 billion to arm Ukraine, the Biden administration has been hesitant about sending the longer-range missile systems Ukraine regards as critical in taking territory back from Russia. As with the debate on no-fly zones in the early period of the war, the focus in the US remains on how best to assist Ukraine without risking dangerous escalation. For Biden, US missiles being used to attack positions within Russia overstep this line.

As a result, there is a distinct lack of clarity on how the US sees the endgame in Ukraine. The Financial Times quotes Stefano Stefanini, Italy’s former ambassador to Nato, that this uncertainty is creating increased anxiety in European capitals:

The Europeans wish they knew what was America’s end game plan, because the idea of Russia losing — or not winning — has not been defined. Does it mean getting back to the pre-February 24 situation? Does it mean rolling back the territorial gains that Russia made in 2014? Does it mean regime change in Moscow?Nothing of that is clear.

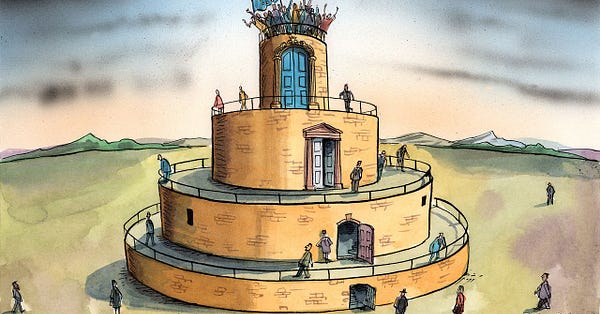

In this vacuum, the Bulgarian political analyst Ivan Krastev argues that European leaders are increasingly dividing into separate camps, on east-west lines:

They are splitting into two broad camps. One is the “peace party”, which wants a halt to the fighting and the start of negotiations as soon as possible. The other is the “justice party”, which thinks Russia must be made to pay dearly for its aggression.

In recent weeks, the leaders of France, Germany and Italy, representing the “peace party” have spoken several times with Putin and called for a ceasefire and peace negotiations, without conceding any territory to Russia. At Davos, Scholz was unambiguous that Putin could not win. Despite this, any talk of peace is dismissed as appeasement by eastern states, particularly Poland and the Baltics:

The Ukrainian position has been more nuanced than these caricatures of appeasement and belligerence suggest, with Zelensky stating in a recent interview with Ukrainian television that he would be satisfied with the pre-invasion status quo and that a Russian withdrawal to those lines could create the conditions for peace negotiations:

“I’d consider it a victory for our state, as of today, to advance to the February 24 line without unnecessary losses. Indeed, we are yet to regain all territories as everything isn’t that simple. We must look at the cost of this war and the cost of each de-occupation.”

Sniping between the West’s “peace” and “justice” parties masks a strategic dilemma that afflicts all sides: absent a clear military breakthrough, how should the war end? Eastern governments accuse Macron, Scholz and Draghi of pursuing peace at any cost. However, the pursuit of a military victory at any cost hinges on the hypothesis that time is on Ukraine’s side and not on Russia’s as the combined effect of sanctions and manpower and equipment shortages cripple Putin’s war effort. Testing this to its limits may place an unbearable burden on the Ukrainian people.

Fatigue

Without clarity on the West’s war aims, the alliance against Putin will continue to fracture. What should its strategic goals be? The starting point should be an acknowledgement of the West’s limits. NATO will not go to war with Russia, and NATO weapons will not be fired into Russia. The resistance of several EU states to a rapid phasing out of imports of Russian fossil fuels constrains further economic pressure on Putin.

The current schisms within the western alliance centre on how far these limits can be pushed. However, no one seriously questions them. Is the UK prepared to send troops to Ukraine? Will the US supply weapons that can hit targets in Russia? The French response to criticism of its attempts to find a diplomatic solution is to argue that If the West is not prepared to go to war with Russia directly it doesn’t have a right to lay down maximalist war aims.

Meanwhile, the EU has finally agreed on its sixth sanctions package, almost a month after European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen announced it would target Russian oil, as well as its biggest bank and multiple media outlets. While the agreed oil embargo will ultimately cover 90% of Russian exports to the EU, it will only be effective by the end of 2022. In the meantime, Putin will continue to receive $23 billion a month in oil revenues from the EU.

The argument that time is not on Russia’s side, and that a combination of western weapons and continued economic pressure will force Putin’s hand is repudiated by the impact to date of the West’s economic war. Absent a global energy embargo that keeps Russian oil within Russia, it is likely to find alternative markets and preserve its financial and military firepower for the foreseeable future.

A seventh sanctions package that included maritime insurance or an EU ban on Greek oil tankers out of Russia might achieve this. However, the growing sense of political fatigue and fracture among EU leaders as the war endures make this an unlikely prospect.

As European governments respond to the growing threat of a global recession and cost of living pressures as food and energy inflation bite, their appetite for deeper and more prolonged sanctions against Russia may wane. The message from the Ukrainian contingent at last week’s World Economic Forum in Davos was that the West must ratchet up sanctions against Russia as a warning to other countries considering using brute force.

Their fear is that under the pretext of diplomatic efforts to end the war that negotiations and compromise will lead to a ceding of territory and an unsustainable peace. There is no evidence that this is what the West envisages. However, it also seems unlikely that it will go much further in military support and economic pressure.

In the meantime, the World Bank estimates that Ukraine’s GDP will fall by 45% in 2022, and the country faces a financing gap of around $5bn every month. The International Monetary Fund has estimated Ukraine's balance of payments gap until June at roughly $15 billion. A major factor is Russia’s stranglehold on the Black Sea port of Odesa, the source of much of the country’s grain exports. At least nearly 25 million tonnes of grain are stuck in Ukraine, according to the UN Food and Agriculture organisation. The impact of the blockade on developing countries that are highly dependent on Ukrainian grains like Egypt, Lebanon, and Algeria is hard to overstate. To date, prices have increased by as much as 50% in some poorer countries. If the blockade endures, the consequences are unimaginable:

Proposals to circumvent the Russian navy by creating a maritime corridor in the Black Sea carry significant escalation risk akin to the no-fly zone NATO has already rejected. While the military battle for the Donbas grinds towards a stalemate, there is a growing sense that the economic war has also reached an impasse on both sides.

Against this background, the clamour for a diplomatic solution will increase. The goal of any such effort should be to create incentives on both sides for a settlement. Italy’s recently circulated peace plan might offer such a blueprint. In addition to a ceasefire, Ukrainian neutrality and a more comprehensive security arrangement between Europe and Russia, the plan proposes that Crimea and the Donbas would become autonomous, self-governing territories within Ukraine.

Any such process will confront all sides with compromises that will be difficult to swallow, and in Ukraine’s case, to receive public consent for. Russia will seek an end to the West’s economic war in return for a cessation of military hostilities. Such accommodations will be excruciating for those rightly appalled by Putin’s aggression. However, in the absence of such a peace, the West's ability to remain united is likely to fracture.

Fables of the Reconstruction

Help with reconstruction and a path towards EU membership for Ukraine will be central to any settlement. The European Commission will deliver its ‘Opinion’ on the membership applications of Ukraine, along with Moldova and Georgia, at the beginning of June.

While it seems likely that the Commission will greenlight candidate status for Ukraine and possibly Moldova, questions about how Ukraine can become a member, how this would change the EU, and how to pay for the rebuilding of its devastated economy and society after the war remain wide open.

Even with candidate status, membership will remain a distant prospect for Ukraine. Accession negotiations cannot begin without unanimous agreement by the EU 27 on the negotiating framework. When negotiations start, any member state can block progress, for example, Greece and Cyprus which are sceptical about fast-tracking Ukrainian membership. Other states are less vocal but equally wary about further eastwards expansion, traumatised by the experience of integrating countries with rule of law issues like Poland and Hungary.

The prospects for disappointment and disillusion on the Ukrainian side are high, while its immediate post-war needs will be great. Getting bogged down in an endless and dysfunctional accession process creates the risk of political instability and division when solidarity will be paramount.

Clearly, the moment requires a new approach to enlargement. French President, Emmanuel Macron’s recent suggestion of a ‘European political community’ which would include non-members and accession countries offers one alternative:

This question remains: how can we organize Europe from a political perspective and with a broader scope than that of the European Union? It is our historic obligation to respond to that question today and create what I would describe here before you as “a European political community”. This new European organization would allow democratic European nations that subscribe to our shared core values to find a new space for political and security cooperation, cooperation in the energy sector, in transport, investments, infrastructures, the free movement of persons and in particular of our youth. Joining it would not prejudge future accession to the European Union necessarily, and it would not be closed to those who have left the EU.

Irrespective of Macron’s intentions, any proposal of an alternative to membership carries the risk of being misinterpreted as a stratagem to keep certain countries out. It will feel like second-class status - the UEFA Cup to the Champions League of membership as the Economist’s Charlemagne columnist puts it:

Ukraine was quick to rebuff Macron’s idea, with Foreign Minister Kuleba saying this could not be a substitute for membership:

If we don’t get the candidate status, it means only one thing, that Europe is trying to trick us. And we are not going to swallow it. Ukraine is the only place in Europe where people are dying for the values the EU is based on. And I think this should be respected.

The question both the EU and Ukraine and other candidate countries will have to confront is how to devise an approach that goes beyond the binaries of today’s unwieldy accession process while avoiding the limbo of discount alternatives. The proposal of former Italian Prime Minister, Enrico Letta, for a “European confederation”, could offer a way forward. It would offer candidates access to the European Economic area and co-ordinate their policies with the EU at a global level on issues like trade, rights and sustainability. Because the current accession process was not designed for a situation like the EU now faces with Ukraine, it should be open to creativity and experimentation in threading this needle.

The other immediate dilemma the EU faces is how to pay for Ukraine’s reconstruction. The cost is likely to reach beyond €500 billion. Here, fables abound. The first is the idea of confiscating Russia’s assets frozen by the EU to fund the rebuilding of Ukraine. Even if a legal mechanism could be found to carry this out, it is difficult to see how such moves could be reconciled with agreeing on peace and an accompanying end to the economic war with Russia.

The second is the notion much in vogue of a “Marshall Plan” for Ukraine. Adam Tooze pours some much-needed cold water on the mythologising of the original. Rather than a magic wand, a relentlessly hard grind to finance the rebuilding of the country lies in store.

A flavour of what awaits was contained in the European Commission’s proposal to set up the ‘RebuildUkraine' Facility as the instrument for the EU’s support for reconstruction through a mix of grants and loans. The facility would become part of the EU budget, like the Covid Recovery and Resilience Fund. However, any questions about further joint borrowing to bolster this effort are off the table. The Commission acknowledges as much, tersely noting that Ukraine’s reconstruction needs are well beyond the means available in the EU budget, meaning that new financing sources will have to be identified.

As ever, the fiscal politics of the EU lag behind the ever-increasing ambitions that its leaders profess for the union - whether it is in defence, energy, technology or health. For now, Ukraine will have to take its place in the queue. How long can it remain there without provoking a dangerous backlash?