Weekend Reading #5

Misunderstanding Putin, Anachronistic Britain, Cranks, Dirty Net-Zero, Farewell the splurge, Urbino, 'Ask not' DC, Grumbling Georgians & Back to the gym

Thank you for supporting Fault Lines. I hope you enjoy this weekend’s most diverting and thought-provoking readings.

The life he has chosen

What the West gets wrong about Putin

We spoke on several occasions between meetings, and he arranged to sit next to me at a dinner, accompanied by his interpreter. At that dinner, he asked me: “What is the single most important obstacle between your Western businessmen and my fellow Russians in starting up business connections?” Off the top of my head, I responded: “The absence of legally defined property rights — without those there is no basis for resolving disputes.”

“Ah yes,” he said, “in your system a dispute between businesses is resolved by attorneys paid by the hour representing each side, sometimes taking the dispute to the courts which normally takes months and accumulation of hourly attorney fees.” “In Russia,” he continued, “disputes are usually resolved by common sense. If a dispute is about very significant money or property, then the two sides would typically send representatives to a dinner. Everyone attending arriving would be armed. Facing the possibility of a bloody, fatal outcome both sides always find a mutually agreeable solution. Fear provides the catalyst for common sense.”

Breaking the nation

The passage (from The Leopard) reminded me of a conversation I’d had with a figure who had been close to Boris Johnson and worried that the U.K. was in danger of becoming an anachronism like the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies or the Austro-Hungarian empire. Britain, this person said, was failing because it had grown lazy and complacent, unable to act with speed and purpose. The state had stopped paying attention to the basics of government, whether that was the development of its economy, the protection of its borders, or the defense of the realm. Instead, it had become guilty of a failed elite groupthink that had allowed separatism to flourish, wealth to concentrate in London and its surrounding areas, and the political elite to ignore the public mood.

The warning is as stark as it is bleak. Austria-Hungary, like the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, had squandered its popular legitimacy after failing to feed, protect, and represent its people equally during its calamitous handling of World War I. As the historian Pieter Judson shows in The Habsburg Empire, Austria-Hungary did not, as is often portrayed, disintegrate because it was illegitimate or a relic of a bygone era. It fell apart because in its desperation to survive World War I, it undermined the foundation of its legitimacy as an empire of nations, becoming instead an Austrian autocracy. In its scramble to survive, it forgot who it was.

Could the same be happening to Britain?

We’re all cranks now

On the internet, we are all encouraged to become the sort of person who writes letters to the editor

I have not, since my father brought home a Compaq Presario in 1995 and plugged it into our phone line, encountered one pocket of space in all of the World Wide Web that does not, to some degree or another, crankify all who inhabit it.

Part of this is just logistics. Online has drastically lowered the barriers of entry into the Order of Crankhood. Time it was when if you really wanted to get publicly steamed about something you’d read, you’d first have to buy a newspaper, read that newspaper, get steamed, go to your writing desk, jot down your letter, put that letter in an envelope, find a stamp, and then walk to the post office. And even after doing all that, there was no guarantee that it would be published. Being a crank even 30 years ago took a kind of monastic dedication to the high art of being a weirdo, but nowadays, saying something deeply unwell about an article you don’t like to thousands of people is as trivial as ordering a coffee.

The dirty way the Net-Zero

Britain's best-kept industrial secret is an unexpected solution to saving the planet

Eliminating greenhouse gas emissions will almost certainly mean doing much of the stuff you're doubtless familiar with: planting more forests and sequestering more carbon; weaning ourselves off fossil fuels for electricity; recycling more - a lot more; using renewable power and electric cars; reducing our demand for energy by insulating our homes and improving the efficiency of industrial processes.

But it will also feature aspects we might be a little less comfortable with: digging vast quantities of stuff out of the ground, racing to secure resources before other countries do; and relying on oil refineries like this, both in the short term and potentially the long term too.

If this might all sound a little unsettling then it's primarily because when it comes to net-zero and how we get there, there are actually two versions of the story: the one the politicians like to talk about and then the one they prefer not to mention. This is about the second version of the story.

Tapped out

Britain’s long consumer binge is ending – and the political fallout will be huge

Under capitalism, for there to be social and political stability, common expectations about living standards need to be satisfied. It’s no coincidence that British consumerism’s best years were also years of relative political calm – or that populism began to take off here, in the late 2000s, when the rise in wages started to stall. Once people feel life is getting too expensive, they often believe everything is getting worse. If enough people feel like that, governments don’t last long.

The light of Italy

The Italian city unchanged since the Renaissance

To get to Urbino today is not all that much easier than it was in the days of Federico.

Unusually for Italy, there's no train station -- the nearest is 45 minutes away at Pesaro. Taking the coach or driving from Florence involves switchback roads as you cross the Apennines and take in three different regions. The nearest airport is 90 minutes away in Ancona, and the closest major city is Bologna, over two hours away.

What that means, though, is that while other Renaissance cities in Italy have been swallowed up by modern suburbs and suffocated by mass tourism, Urbino has been left blissfully intact.

"A tourist coming to Urbino has to really want to come here, so it's unique in how it's been preserved from 'hit and run' tourism," says Luigi Gallo, director of the Galleria Nazionale delle Marche, the art gallery which sits inside Federico's ducal palace.

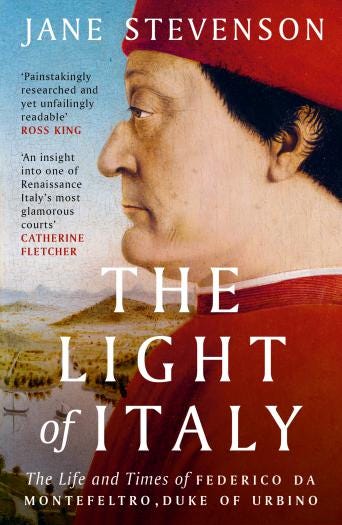

If this whets your appetite, make sure to get Jane Stephenson’s wonderful and stunningly illustrated celebration of Urbino and the Montefeltro clan.

The Life and Times of Federico da Montefeltro, Duke of Urbino

Drained

The nation’s capital is the most public-spirited city in the country. By far.

The gross excesses of America’s money culture are much more pronounced in New York, Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Houston. Power struggles take place in Washington, but they take place, too, in Pittsburgh, Des Moines, Santa Fe, and everyplace else where humans dwell. Sneering at the untutored masses, something MAGA types imagine to be D.C.’s favorite pastime, is actually far less common in Washington than in any major city I can think of; the vice that usually takes its place, a certain piousness about the deeper wisdom of the American People, is, by comparison, pretty benign. Yes, there are cynical corporate lobbyists looking to corrupt the tax code, but there are also plenty of decent folks lobbying their hearts out for more affordable housing or cleaner air and pulling down maybe $80,000 for their troubles.

Washington is a much more powerful magnet for public-spirited people who want to make the world a better place than it is for sleazy people who want to drown the globe in carbon emissions and multigenerational family trusts. (The sleazy types can usually do better elsewhere.) Washington is a place where people, in Robert Kennedy’s famous reformulation of George Bernard Shaw, “dream things that never were and ask why not.” Some of those dreams are plausible, and some are not. But I’ve never seen anyplace else where so many idealistic people allow their visions of a better society to govern their everyday lives. There isn’t much point coming here if you don’t.

The worst of times

What Driveling Times Are These!

Grumbling is, after all, a human reflex, especially among the ill and embittered. In 1769 one commentator announced (without proof) that “we are almost universally unhappy.” Farmers who were subject to the vagaries of the weather were particularly famous complainers. The touring missionary John Wesley noted that characteristic in 1766. Observing the country farmers, he remarked, “In general, their life is supremely dull, and it is usually unhappy too.”

Yet townspeople were also vociferous in complaining. “Gloom and misanthropy have become the characteristics of the age in which we live,” mourned Percy Bysshe Shelley in 1817, temporarily downcast by the weakness of reform campaigns. Getting into the market for pessimism, a poet in 1840 versified eloquently about the current Age of Lead, declaiming: “What doleful days! What driveling times are these!”

Post-Pandemic

Peloton’s problems aren’t just Peloton’s

But Peloton’s demise also coincides with a trend in more people working out like they used to do: at gyms. Demand for in-person fitness classes and gym memberships has rebounded, while Google searches for home gym equipment overall have continued to fall since their high in March of 2020. Foot traffic to gyms has now returned to the same levels as January 2020, according to data from SafeGraph, a geospatial data company. Planet Fitness alone said that, by November, it had recovered 15 million customers, which amounts to just half a million customers fewer than its pre-pandemic peak.